A Narrative Lectionary Sermon on John 2:1-11

John 2:1-11

On the third day there was a wedding in Cana of Galilee, and the mother of Jesus was there. Jesus and his disciples had also been invited to the wedding. When the wine gave out, the mother of Jesus said to him, “They have no wine.” And Jesus said to her, “Woman, what concern is that to you and to me? My hour has not yet come.” His mother said to the servants, “Do whatever he tells you.” Now standing there were six stone water jars for the Jewish rites of purification, each holding twenty or thirty gallons. Jesus said to them, “Fill the jars with water.” And they filled them up to the brim. He said to them, “Now draw some out, and take it to the chief steward.” So they took it. When the steward tasted the water that had become wine, and did not know where it came from (though the servants who had drawn the water knew), the steward called the bridegroom and said to him, “Everyone serves the good wine first, and then the inferior wine after the guests have become drunk. But you have kept the good wine until now.” Jesus did this, the first of his signs, in Cana of Galilee, and revealed his glory; and his disciples believed in him.

The Message

Today is the day when the church, universal, celebrates Jesus’s baptism. But in the gospel according to John, Jesus’s baptism is never covered. It’s never mentioned—not even once. We see Jesus’s cousin, John the Baptist, harkening back to the words of the Prophet Isaiah, testifying to crowds of locals as he baptizes them. John the Baptist insists to priests and to Levites sent from Jerusalem that he is not the Messiah; that the Messiah is coming. But we never see that messiah—Jesus—baptized, himself.

Today, we focus, instead, on Jesus’s first miracle. The first public act in his almost three-year-long ministry. This story of the wedding at Cana is well-known and well-loved, and I think it makes sense to read as a stand-in for a baptism story. After all, on the surface level, it centers around water and transformation. It’s a story about a lavish gift from God that eliminates shame. Jesus gave a gift here, regardless of merit—regardless of what people did or didn’t deserve. The act of turning water to wine is an act that boasts the glory of God above all else.

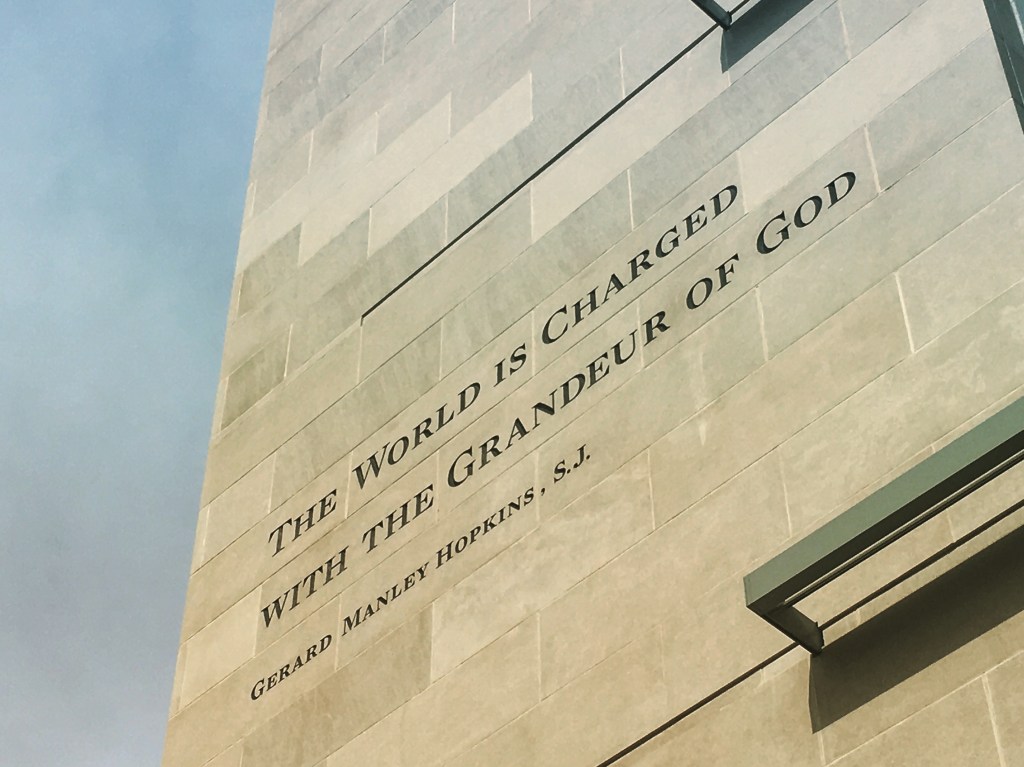

Glory is a very, very Johannine theme. Who doesn’t love a little glory?

But friends, on a deeper level, this story makes sense to read on the day we remember Jesus’s baptism because it reminds us why that glory actually matters. And what do I mean by that, exactly?

Well, we have walked through most of Chapter One of the book of John – through the prologue and the calling of Jesus’s disciples. This has given us a feel for John’s style and John’s agenda in his writing.

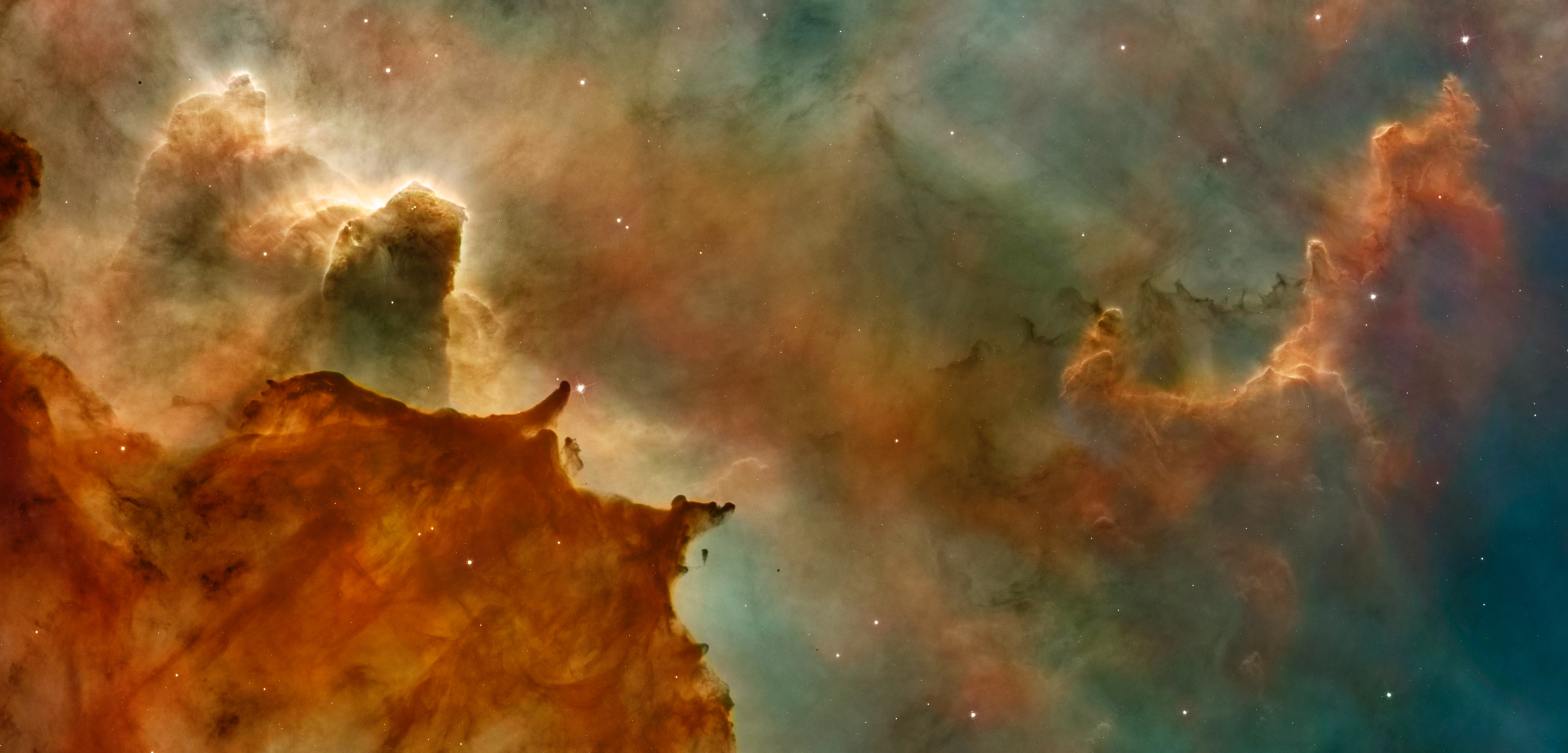

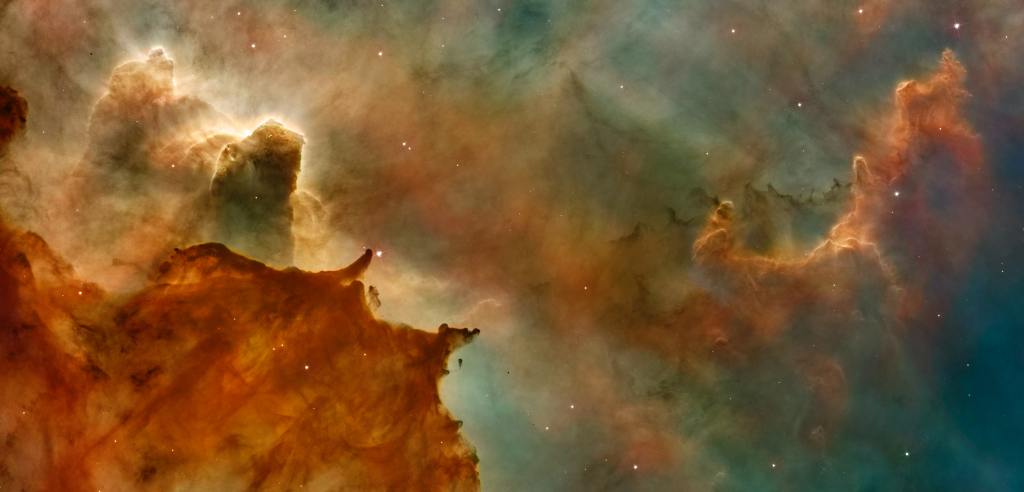

I think it’s fair for all of us to say that John is a bit of a drama king. He goes big about everything. Cosmic, even. To use the words of an old professor of mine, John’s gospel is the gospel where Jesus is only ever incredible, up close and entering the scene with perfect lighting and a fog machine.

It’s easy for us to get swept up in the grandeur of John’s writing—the omniscience and the total control that God and Jesus seem to have throughout the gospel.

I think that, in the gospel of John, it’s easy for us to accept a bias toward the divine side of Jesus’s divine and human nature. To burrow into glory for glory’s sake, alone.

I think that, when we read John, it’s easy for us to stop asking questions about the text. To find solace in really abstract ideas—really abstract mantras—and just stop there.

This miracle story is one of the great balancers in John’s approach. I think that it swings the pendulum back toward a human bias. When I say that this story reminds us of why God’s glory actually matters, I mean that it reminds us of why God’s glory actually matters for us.

The story of the wedding at Cana keeps us from getting swept up in grandeur. It helps us start asking questions again. It makes sure we don’t stop at the abstract. It makes sure that we let ourselves dig into some messy details. And if all of you are feeling up to a little thought experiment this morning, I want to explore that idea by retelling this story through the lens of Mary.

Mary has to be crucial to our interpretation of this passage. Otherwise, there would be no reason for John to have included her. Think about it. If Jesus really is the star of the show in this gospel—if he is incredible, up close with perfect lighting and a fog machine—you would think that he would milk the moment when he transitions from someone who has been foretold to someone who is actually here doing the work of God. You would think that he had a plan behind performing his first miracle. But the text doesn’t read that way.

It doesn’t even read like Mary and Jesus came to this wedding together. It says that Mary was there, and that Jesus and his disciples had been invited, too. Mary comes up to Jesus and says, “They have no wine.” We assume this is because she thinks he’ll be able to fix that. This is the most Minnesotan version of Mary I think we ever see. It’s not, “Honey, help them figure out what to do about the wine,” or, “Honey, you’re the Messiah. If anyone can pull off a miracle here, it’s you.” No. She goes for a very simple, “They have no wine.”

Jesus says to her, “Woman, what concern is that to you and me? My hour has not yet come.” Now, in English, this sounds pretty rude. “Woman,” alone, is an abrasive address to our ears. But Jesus refers to a lot of other female figures in the gospel of John this same way. “Woman.” It’s unusual that he would choose this word for someone as intimate as his mother, but in the Greek, this title in general is more indifferent than it is rude. It’s not really charged any one way.

As for the sentiment about his hour, the direct translation is something like, “What to me and to you?” Once again, this is striking, and not typical as an exchange between parent and child, but not necessarily as harsh as it comes across to us. It’s mostly neutral.

I am amazed by Mary’s reaction every time I read this story. Rather than getting flustered; rather than trying to convince Jesus to care; she actually returns his indifference. She puts the ball entirely in his court. She goes to the servants at the wedding and says, “Do whatever he tells you.” Which has to mean that she has a hunch he will come around.

We’ll never know for sure what inspires Jesus to change his mind and provide for the bridegroom and all of the guests, but we do know for sure that Mary’s words and Mary’s faith in who Jesus is—in what she knows he can do—seem to make a difference here. Sure, the wedding is saved and Jesus is officially outed as a fulfillment of the prophecies and rumors that have been swirling around Galilee. But I actually think that the biggest difference we should care about this morning is the difference that Mary’s words and Mary’s faith created for herself.

Mary’s instigation of this miracle is her first step in acknowledging the fact that she is going to lose Jesus. Mary’s coy little invitation to Jesus at this wedding feels to me like her giving herself permission to start the struggle of accepting his call.

You know, as of a few months ago, it has become drastically easier for me to empathize with Mary. To connect with her as a figure in our shared history. To try to put myself in her shoes. My body is going through the nausea and the bloating and the breakouts and the aches and pains and the shape shifts of pregnancy. I wonder if hers did, too. My mind has gone to places it’s never gone before, curious and terrified about hypotheticals that I’ve never had to imagine. I wonder if hers did, too. This baby is only halfway to being here, but already, she has brought out opinions and extreme convictions from so many people in my community and George’s. I’m willing to bet that Mary had it a million times worse in that department. The main difference I’m recognizing between Mary’s experience and mine—minus about two thousand years’ worth of medical technology, of course—is the fact that I get to imagine what an entire life might look like with my child. I endure these things and welcome these changes because I have a chance to live a life of faith alongside my daughter. George and I get to hope for a shared lifetime with her.

Mary never got to do that. For her, living a life of faith meant, from the beginning, that she would have to let go of her son in multiple senses of the term. That she would outlive him. That she would watch him journey through the highs and lows of a misunderstood and very public life, and that she would only be able to help so much.

I wonder how often Mary was tempted to wrap her arms around Jesus and to tell him that it was okay for him to stay at home a little longer if he wanted to. That it was okay to take a new construction project or put some more thought into who he wanted to gather as his disciples. That he didn’t have to rush anything. I wonder how many times she had to resist the urge to stall him; to keep him close and cherish the extra seconds and minutes she could conjure up.

In our story this morning, Mary is doing the hardest thing she will ever have to do. The most human thing she will ever have to do. She is letting Jesus know that as he launches into his work, she will launch into hers. She believes enough in who he is and what he is sent to do that she will center him—who is he, and what he is sent to do—in her life. She believes enough in the true glory of God that she is willing to wander into the not-so-glorious.

During the wedding at Cana, Mary is letting Jesus know that she understands that he has been sent to quench thirst in more ways than just this.

Here’s a tangent I think is interesting—the only other time Mary is mentioned in the gospel of John is at the crucifixion.

When Christ was baptized, he was baptized into death. This is what we profess. When we are baptized, we are baptized into death with him, so that we may find new life. Not just once, at the end of our respective worlds, but every. Single. Day. Sometimes multiple times a day.

Because we follow the Narrative Lectionary, I always want to weave the Hebrew Bible into our message. The Psalm associated with this passage from John in our liturgy is Psalm 104, and there is a relevant passage I want us to meditate on as we wrap up our worship today:

“You, God, cause the grass to grow for the cattle,

and plants for people to use,

to bring forth food from the earth,

and wine to gladden the human heart,

oil to make the face shine,

and bread to strengthen the human heart.

The trees of the Lord are watered abundantly,

the cedars of Lebanon that God planted.

In them the birds build their nests;

the stork has its home in the fir trees.

The high mountains are for the wild goats;

the rocks are a refuge for the coneys.

You have made the moon to mark the seasons;

the sun knows its time for setting.

You make darkness, and it is night,

when all the animals of the forest come creeping out.

The young lions roar for their prey,

seeking their food from God.

When the sun rises, they withdraw

and lie down in their dens.

People go out to their work

and to their labor until the evening.

O Lord, how manifold are your works!

In wisdom you have made them all…”

Friends, the glory of God that shines through these seasons of Christmas and Epiphany is anything but superficial. Anything but empty. Glory is not a one-sided experience. It’s not wonderful just because it’s wonderful. It’s wonderful for us because we know what things can look like and how hard things can be when we don’t feel connected to it. When it seems far away, or invisible. Or impossible.

We should not leave this place today consoled by the fact that our God provides us with lavish gifts. That’s true, and it’s very nice. But it’s not satisfying, and it’s not enough. We should leave this place today consoled by the fact that we have a God who knows literally as well as we do how challenging it can be to navigate this world, and who will never abandon us as we keep trying to.